School feeding managers and staff from World Food Programme (WFP) offices in Angola, Timor-Leste, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe and Brazil participated, on Tuesday, August 23, in an online dialogue on best practices in nutrition and main challenges in the implementation of school feeding programmes. The event, promoted by the WFP Centre of Excellence against Hunger in Brazil, in partnership with the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC) and the National Fund for Education Development (FNDE), promoted the exchange of experiences and opportunities for collaboration between participating countries.

At the opening session, Plinio de Assis Pereira Junior, from the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC), spoke about the importance of South-South Cooperation in advancing school feeding in Portuguese-speaking countries. Then, Gracy Heijblom, from WFP in Angola, presented a digital tool for creating school menus used in the country. The tool allows professionals to adapt menus according to localities and the target audience, to calculate micronutrients, the cost for each meal and food profile, including values for energy, protein, lipids, and carbohydrates. “The tool enables flexible calculation to adapt these menus to the beneficiaries, so we can manage the programme more quickly and efficiently,” she added.

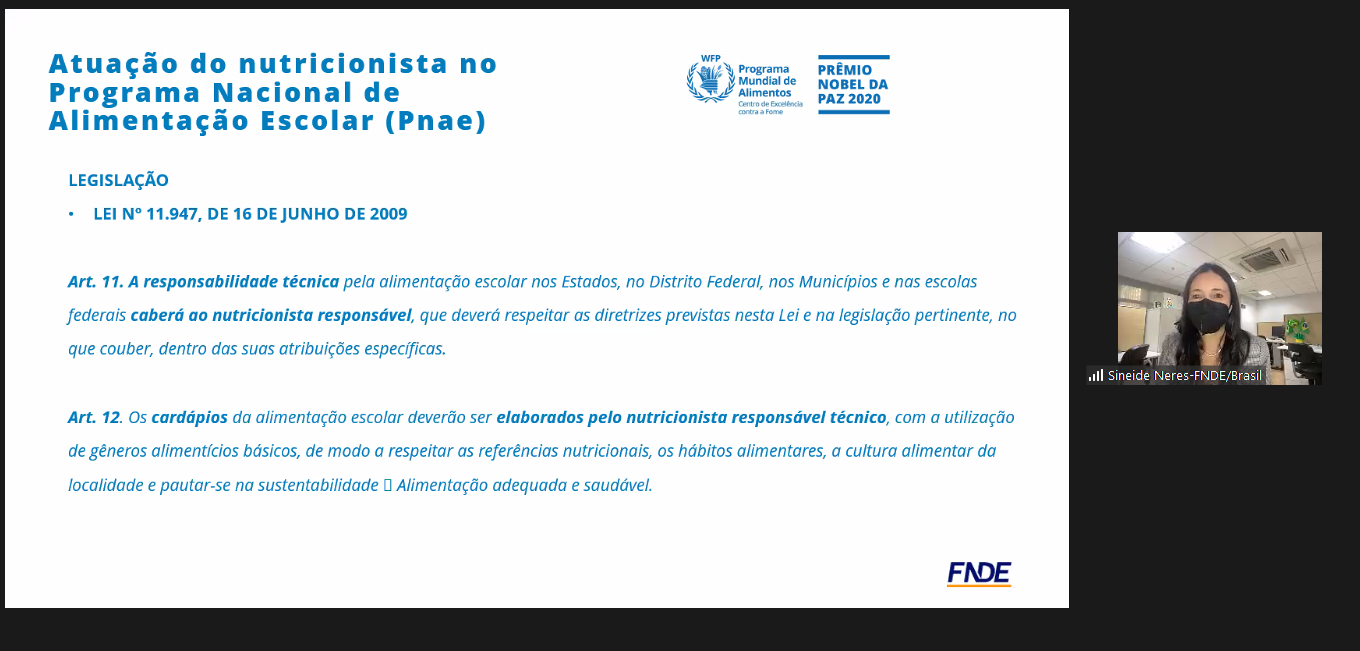

The Brazilian experience was presented next, with the participation of Sineide Neres, Advisor to the General Coordination of the National School Feeding Programme (PNAE). She said that, throughout its 60 years of existence, the PNAE has been through several changes and today it requires the presence of at least one nutritionist in each school, with responsibilities that go beyond the preparation of the menu, including: coordination of the programme’s activities in the states and municipalities, conducting menu acceptability tests and training for school cooks. “The menus consider regional specificities, student weight and height, individual pathologies history and eating habits of specific groups, such as indigenous and quilombolas,” said Sineide Neres.

The Brazilian experience was presented next, with the participation of Sineide Neres, Advisor to the General Coordination of the National School Feeding Programme (PNAE). She said that, throughout its 60 years of existence, the PNAE has been through several changes and today it requires the presence of at least one nutritionist in each school, with responsibilities that go beyond the preparation of the menu, including: coordination of the programme’s activities in the states and municipalities, conducting menu acceptability tests and training for school cooks. “The menus consider regional specificities, student weight and height, individual pathologies history and eating habits of specific groups, such as indigenous and quilombolas,” said Sineide Neres.

Sebastiana Nani Lemos, the school feeding focal point at the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (MEJD) of Timor-Leste, presented a brief history of the programme, which began in 2005 as a WFP pilot and, in 2011, was taken over by the country’s government. Currently, the programme serves children from 5 to 12 years of age in 13 municipalities, totalling 320,000 children, or 24% of the country’s population. “The programme is one of the main elements of the social safety net and supports the food security of families and children,” said Sebastiana Lemos. Among the challenges mentioned are the increase in the price of food and fuel, a decrease in the budget for school feeding, as well as challenges in monitoring and standardizing data collection.

Opening the second presentations session, Pita Correia, from WFP in Guinea Bissau, in partnership with representatives of the Directorate-General of the School Canteen, explained that the programme was launched in 2000 and now serves students from 6 to 11 years of age. The School Canteen Act adopted by the government in 2019 determined the inclusion of food and nutrition education activities in schools and the distribution of take-home rations. Among the main challenges faced by the country are difficulties in calculating the menu and the scarcity of nutritionists. The country is now working on volunteer training, local food purchases and digitization projects.

In Mozambique, the national school feeding programme serves 215,000 students in 340 schools in 42 districts, covering 30% of daily energy needs and 20% of micronutrient needs. According to Manuel Veremo Fulede, Technician of the Department of Nutrition and School Health of the Ministry of Education and Human Development, the programme has as its pillars the improvement of the nutritional status of students, the promotion of food and nutrition education in schools and the development of agricultural skills. “We are developing a manual that will be distributed to schools and local communities, making the connection between agricultural production, also contemplating school gardens,” he said. The country is also currently working on food fortification programmes to combat micronutrient deficiencies.

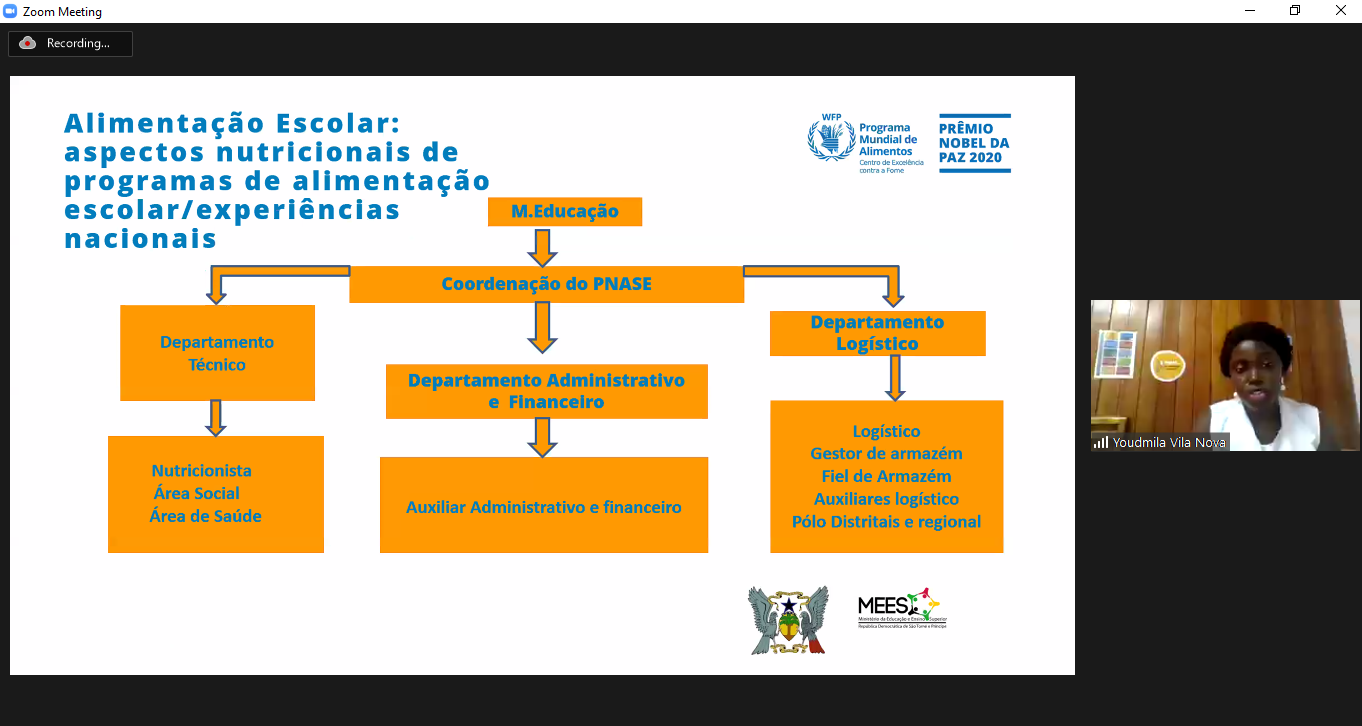

At the last country presentation, participants were able to learn more about the experience of the school feeding programme in São Tomé and Príncipe, which was created in 2010. Until 2015, WFP provided support for the programme, which started to be fully run by the government in 2016. According to Youdmila Vila Nova, Nutritionist of the National Programme for School Feeding and Health, the programme aims to strengthen nutrition and create healthy habits, serving about 50,000 students between 3 and 14 years of age, which corresponds to 25% of the national population. The challenges include monitoring and evaluation, high prices of local goods compared to imported food, logistics and the lack of law regulating the purchase of local products.

In addition to country interventions, Eliene Sousa, from the WFP Centre of Excellence against Hunger in Brazil, presented the Nurture the Future project and outlined an overview of the state of nutrition in the world, pointing out challenges and opportunities for governments and partners.

Throughout the presentations, participants were able to ask questions about shared challenges and good practices that could be adapted in their countries, on topics such as menu preparation, financing, monitoring and a holistic approach that considers issues ranging from malnutrition to obesity. “The challenges were also common, especially in infrastructure, logistics, investments and government commitment,” said Christiani Buani, from the Regional Centre of Excellence against Hunger and Malnutrition in Côte D’Ivoire (CERFAM), as she summarized the session.

“We need to show that school feeding programmes are investments. They will lead to economic return for the populations of each country. Children will be able to learn more, and at the same time, we have agricultural development because we buy locally,” said Daniel Balaban, Director of the WFP Centre of Excellence against Hunger in Brazil, in his closing remarks. “It’s a health programme, because a nurtured child is also not going to have diseases related to a poor diet, and it’s also a social and economic development programme,” he added.

The countries will meet again by the end of this year for the second session of the talks, this time focusing on school feeding and family farming purchases.